Thirty-two Marks of Excellence

Also referred to as the “thirty-two major marks” and “marks of a great man,” these are the characteristics of excellence adorning Buddhas and wheel-turning monarchs.

Also referred to as the “thirty-two major marks” and “marks of a great man,” these are the characteristics of excellence adorning Buddhas and wheel-turning monarchs.

Many different sutras contain descriptions of the thirty-two marks and eighty characteristics, each with slight variations:

Top of his head not visible to others.

A prominent nose with well-concealed nostrils.

Eyebrows shaped like a new moon.

Large, round ears that are long and thick.

A strong body.

Closely-fit bones.

When he turns, his whole body turns, just like a majestic elephant.

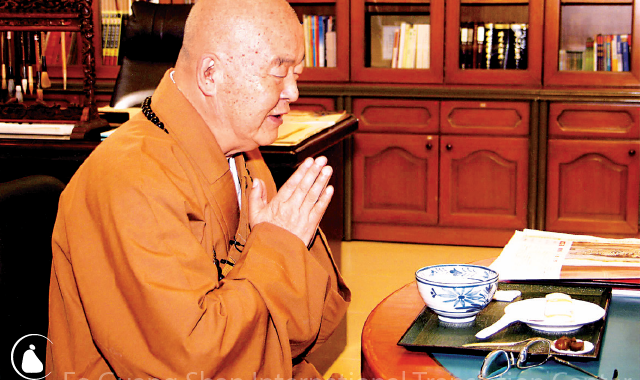

It is my hope that our Buddhist monks will all become monks who give support in all directions and not become monks who live off all directions. Whoever it may be, the monastic followers or the lay disciples, although we have not yet attained enlightenment, we can still broadly make affinities with others first, so as to become aspiring bodhisattvas who will ensure that “Buddhism depends upon [us],” and not have ourselves become dependent upon Buddhism.

It is enough for most monks to

only have the ability to chant and

teach the Dharma, and of course I

too can chant sutras and teach the

Dharma. But only being this kind

of monk was not something I was

willing to do. I wanted to become

a monk who was able to engage

in propagating the Dharma in a

multifaceted

way: There is nothing

I would not do, as long as I am capable

of doing it and as long as it is

related to Buddhism.

At the many places I engaged in practice and study—at places such as Qixia in Nanjing, Jinshan and Jiaoshan in Zhenjiang, and Tianning in Changzhou, where I was brought up experiencing spring breezes, summer rains, autumn frosts, and winter snows—I studied silently and grew up quietly. I was always thinking as to how I could repay Buddhism’s kindness. I could not make a living by depending on Buddhism over the long term. I ought to make some contributions to Buddhism—this was the idea that developed in me from a young age.

The Avatamsaka Sutra says, ‘The mind controls everything.’ In order to properly control body and speech, we must come to understand our minds. If we can control our minds, we can do anything. Master Xingkong (780-862) wrote a wonderful passage that expresses this point very well. He said, “The practice of Buddhism can be compared…